November is Native American Heritage Month, which seems as good a time as to address, at least in part, the role our ancestors played in the treatment of the Native American people who were already living in New England before they arrived. Growing up, talk of conflicts between Europeans and American Indians for me at least evoked cavalry charges against Souix warriors galloping across the Great Plains, whereas New England conjured up scenes of smiling people with feathers in their hair and buckles on their hats exchanging corn and pies in a quaint display of cultural appreciation.

In fact, seventeenth century colonial New England witnessed two bloody wars between the colonists and the indigenous population. The first of these – the Anglo-Pequot War of 1636 to 1638 – took place in Connecticut, and was the very first large-scale conflict between English colonists and the indigenous people of North America north of Mexico. At least two of our ancestors were directly involved in one particular watershed event that was once commonly called the Battle of Mystic Fort, but is now more often – and more appropriately – known as the Mystic Massacre. This event made possible the colonization of Connecticut and set the stage for the expansion of the English colonies in New England. Some historians and legal scholars have also argued that the event, and what subsequently befell the Pequots, qualifies as genocide.

Thomas Hooker and the founding of Hartford

When our immigrant ancestor William Backus arrived in Saybrook sometime in the 1640s, he was a relative latecomer when it came to the first wave of English migration to the New World.

Most English families arrived earlier during a massive wave of English immigration that took place in the 1630s known as the Great Migration, which saw the arrival of about 20,000 settlers from England between 1630 and 1640. These immigrants were largely puritans seeking to escape the religious persecution of Charles I. By the 1640s this migration was largely halted when the puritans stopped fleeing and started fighting in the English Civil War.

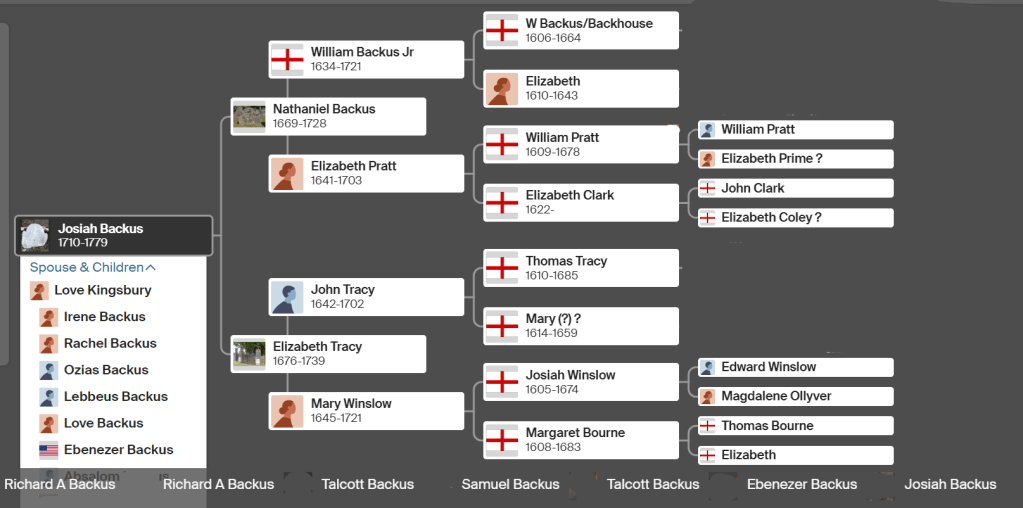

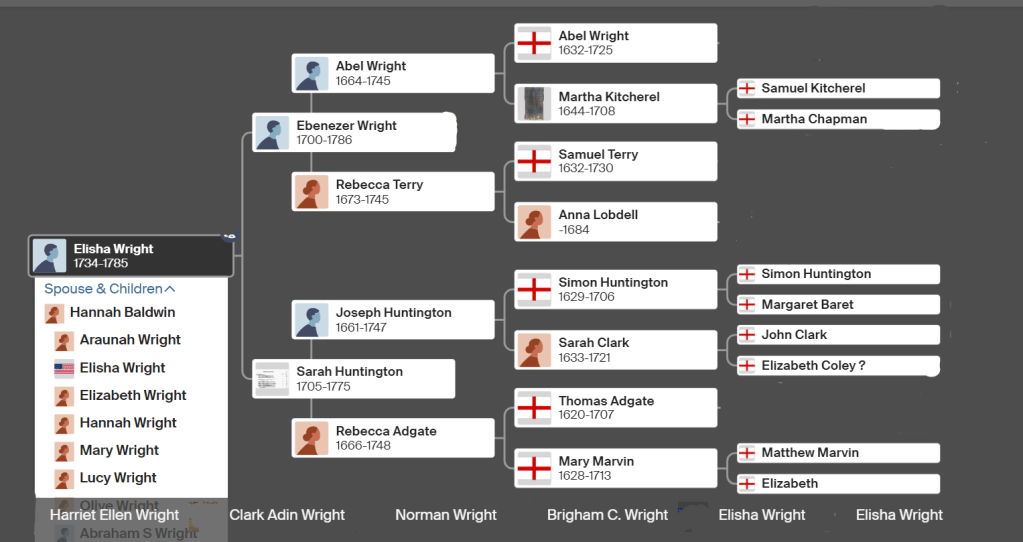

Two such ancestors were John Clark and William Pratt. Clark’s daughter, Elizabeth, married William Pratt, and their daughter Elizabeth was the second wife of William Backus, Jr – the son of the original Backus immigrant ancestor of the same name. On our Wright side of the family, John Clark is also an ancestor through another one of his daughters, Sarah. See below:

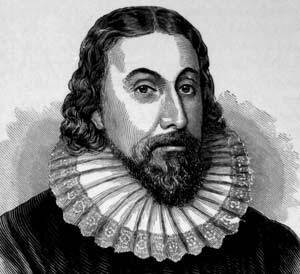

Both William Pratt and his future father-in-law John Clark hailed from County Hertfordshire in England. How they came under Puritan influence is not precisely known, though Pratt was likely the son of Reverend William Pratt of Stevenage, who studied at Emmanuel College in Cambridge, a hotbed of Puritan theology where two of the most influential New England theologians studied, John Cotton and Thomas Hooker. It was Hooker who Clark and Pratt would ultimately tie their fortunes to when both men emigrated to the recently established Massachusetts Bay Colony. We know Clark arrived in Massachusetts in 1632 – possibly on the Griffin with Cotton and Hooker – and Pratt likely arrived in 1633.

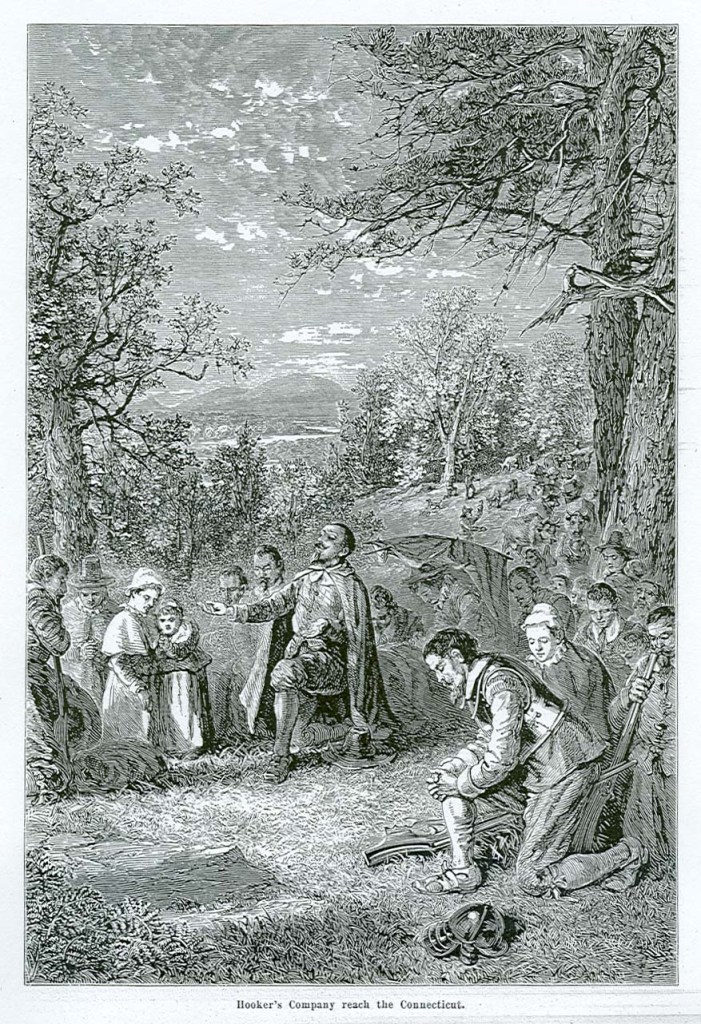

Once in New England, Cotton and Hooker fell out with each other over suffrage rights in the colony: Cotton maintained that only full-fledged members of the church should be allowed to vote – and then only after a rigorous religious examination – while Hooker wanted suffrage to be extended to all Christians (needless to say, no one entertained the idea of non-Christians being a part of this new society). This dispute led Hooker to lead a group of about a hundred colonists inland to found a new settlement on the Connecticut River in 1635. Both Clark and Pratt would join this group shortly thereafter, and all three would become founders of Hartford, the city that would become the center of the Connecticut Colony and the current state capitol.

The Pequots

Standing in the way of this colonial destiny was the fact that people had been living in Connecticut for thousands of years before the arrival of European colonists. When the English started to make their way into central Connecticut, the region was dominated by the Pequots, who were centered in Eastern Connecticut but had recently subjugated most of the other tribes around them. Also preceding the English in the region were the Dutch, who, moving west from New Amsterdam, had already established a trade agreement with the Pequots and a fort directly across the river from Hartford (idyllically named Huys de Hoop or “House of Hope”). The Dutch were there for trade – specifically to expand their control of the North American fur trade which had been so lucrative for them in the Hudson River valley.

Relations between the English colonists and the Pequots got off on the wrong foot when either the Pequots or one of their tributary tribes killed an English trader named John Stone. The Pequots tried to smooth arrangements with the English, which resulted in a trade agreement between the Pequots and the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and which allowed for the establishment of the Connecticut River colonies of Windsor (1633), Wethersfield (1634), and Hartford (1635). Although negotiations over the death of Stone never were resolved, things seemed to be on the upswing for Ango-Pequot relations, and the Massachusetts Bay Colony even managed to secure a peace treaty between the Pequots and their regional enemies to the east, the Narragansetts.

Hostilities Begin

But peaceful coexistence was not to be. The pressure created by the rapidly increasing number of English immigrants into North America – and the land and lucrative trade that the Pequots stood in the way of – made conflict inevitable, beginning a cycle that would be repeated over and over again over the next two hundred and fifty years of American history. The rapid increase in the population of the colonists made the largely uncolonized region of Connecticut appealing, but the Pequots controlled more than just the land. Because of their domination of the Connecticut coast, the Pequots also largely controlled the manufacture of wampum, jewelry created from white and black shells gathered from the Long Island Sound. Wampum was instrumental in trading for fur with Native American tribes in the interior. The importance and value of wampum, and the control of its production, is evident by the Massachusetts Bay Colony declaring it a form of legal tender in 1637 valued at six beads a penny.

The triggering event was the murder of another English trader, John Oldham, in 1636 by the native inhabitants of Block Island. Block Island was Narragansett territory, enemies of the Pequots to the east in what is now Rhode Island, and the Narragansetts swiftly sent a delegation to Boston to assuage the colonists, pay restitution, protest the innocence of the Narragansett chiefs, and declare that the true perpetrators of the murder were being given refuge by the Pequots. In response, the government of Massachusetts sent out a fleet of small vessels carrying a force of 90 armed men under the command of John Endicott – despite the fact that there was no real evidence of Pequot culpability in Oldham’s murder.

Endicott’s specific orders were first to sail to Block Island, slaughter all of the adult men there, seize the women and children, and then claim the Island for Massachusetts. All didn’t go according to plan, however, as the natives escaped and hid in the swamps, so Endicott’s men had to satisfy themselves with burning down the village and its crops, staving the canoes out to sea, and shooting some of their dogs. Their next order of business was to go to the Pequots and demand they hand over the murderers of John Stone two years earlier along with “other English” and either one thousand fathoms of wampum or twenty of their children as hostages until the restitution could be paid (the fact that Oldham wasn’t even mentioned by name indicates how flimsy the immediate provocation on Block Island was when it came to confronting the Pequots.) Arriving in Connecticut, Endicott gave his ultimatum and waited as the Pequots stalled for time while they slipped away. With the natives eluding him, Endicott had to once again content himself with ravaging the country and burning their crops. He then returned to Boston.

Endicott’s expedition was met with little enthusiasm from the colonists in Connecticut, for they correctly understood that they, rather than Massachusetts, would bear the brunt of the Pequot retaliation. This came to pass: the Pequots commenced a series of attacks on English settlers in Connecticut and besieged Fort Saybrook. Realizing this was going to be serious business, the Pequots also sent a delegation to their rivals the Narragansetts with a proposal to set aside their differences and form an alliance to drive the English from the region. The Pequots seemed to understand that they were no match for English on the open field against their guns, but they argued that they could wage a successful campaign where they would set fire to their houses, destroy their crops and livestock, and generally harass them and make their lives so miserable that they would have no choice but retreat back across the ocean from where they came from. Finally, in a moment in prescience, they appealed to the Narragansetts to realize that if the Pequots were destroyed, they themselves would not be far behind.

This delegation opens up a great “what if’s” of American history. There were probably fewer than ten thousand colonists in New England and less than a thousand colonists in Connecticut at this time, a number that would expand dramatically once the colonists had secured a stable footing in the region. Could a Pequot-Narragansett alliance have, if not driven them from the coast of Massachusetts, at least forestalled their rapid expansion westward until the Great Migration dropped down to just a trickle in the 1640s? We’ll never know for sure: though Narragansetts apparently took the Pequot proposal seriously, they were persuaded – largely at the behest of Rhode Island founder Roger Williams – to reject an alliance with their traditional enemies and side with the colonists. Thus the Pequots found themselves not only isolated, but now at war with a coalition of powers that included the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Connecticut colonists, the Narragansett nation, and most of the tributary tribes that were eager to shake off their control.

In April 1637, the Pequots and their allies attacked the small village of Wethersfield – just about five miles south of Hartford – killing nine colonists and kidnapping two teenage girls who they hoped would be able to teach them how to make gunpowder (they couldn’t). This action roused the colonial leaders in Connecticut to take action. The three Connecticut River settlements raised a military force of 90 men (90 seems to have been the magic number for colonial military operations) in order to commence an offensive war against the Pequots. Our ancestors John Clark and William Pratt were among the forty-two men who enlisted from Hartford.

The Mystic Massacre

The man leading the expedition – Captain John Mason – was a seasoned professional soldier and veteran of Europe’s Thirty Years War, serving under Sir Thomas Fairfax in some of the major battles and campaigns against the Catholics in the Netherlands during the 1620s. Mason arrived in Massachusetts in 1632, and his military expertise was quickly put to use in building a fort in Boston Harbor and commanding a small fleet to chase off the first pirate to prey on New England waters, Dixie Bull. In 1635 Mason settled in Windsor, Connecticut, becoming an obvious choice to command the military force raised by the Connecticut River colonies. In that role he would prove to be capable, efficient, and ruthless.

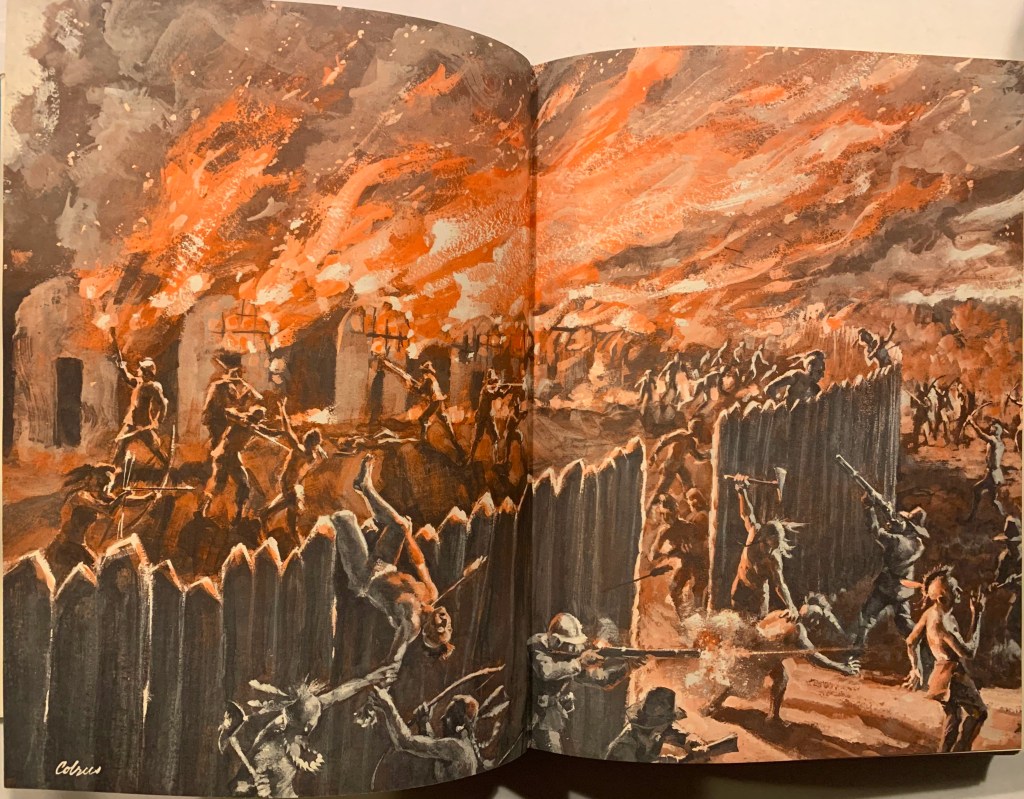

Joining him were seventy Native American warriors under the command of Uncas, the sachem of the Mohegans, tributaries of the Pequots who were in open rebellion against them. This combined force first marched to Fort Saybrook to relieve the siege, and there was joined by another twenty soldiers under the command of Captain John Underhill, another hardened veteran of Europe’s religious wars. Mason and Underhill recruited another 200 or so Native American allies from the Narragansetts before marching into Pequot territory, arriving at a palisaded village on the Mystic River on the evening of May 26, 1637. It seems the Native American allies were dubious of the colonists’ resolve in attacking the fearsome Pequots. In a “hold my beer” moment, Mason told his Indian allies to step back and watch, then he and his men proceeded to attack the fort right before dawn.

Initially, the plan was to sneak into the settlement, kill the inhabitants, and “save the Plunder”. But a barking dog alerted the sleeping Pequots to the infiltration, and only twenty colonists were able to penetrate the village before a stiff resistance was put up by the defenders. Mason, seeing his men scattered under arrow fire, then decided to try a different tactic. In his published account of the battle, Mason describes his actions in the third person:

The Captain also said, WE MUST BURN THEM; and immediately stepping into the Wigwam where he had been before, brought out a Fire-Brand, and putting it into the Matts with which they were covered, set the Wigwams on Fire.

Mason and his men withdrew and encircled the fort, with his Narragansett and Mohegan allies forming an outer ring behind them. Captain Underhill gives a description of what happened next:

many were burnt in the Fort, both men, women, and children, others forced out, and came in troopes to the Indians, twentie, and thirtie at a time, which our souldiers received and entertained with the point of the sword; downe fell men, women, and children, those that scaped us, fell into the hands of the Indians, that were in the reere of us; it is reported by themselves, that there were about foure hundred soules in this Fort, and not above five of them escaped out of our hands.

By all accounts it was a slaughter. Underhill gives the death count at 400, while Mason says it could have been as high as 700, mostly women, children, and elderly non-combatants. Only two colonists were killed in the battle. Both Mason and Underhill, probably reflecting the views of most of the colonists at the time, saw themselves as the sword of righteousness in executing God’s will.

In the words of Mason:

GOD was above them, who laughed his Enemies and the Enemies of his People to Scorn, making them as a fiery Oven…Thus did the LORD judge among the Heathen, filling the Place with dead Bodies!

And in the words of Underhill:

Why should you be so furious (as some have said) should not Christians have more mercy and compassion?…sometimes the Scripture declareth women and children must perish with their parents; some-time the case alters: but we will not dispute it now. We had sufficient light from the word of God for our proceedings.

The Aftermath

After the massacre, the Pequots were on the run. The Pequot sachem Sassacus attempted to flee west with about 400 followers out of Connecticut, but the English and Mohegans caught up with them at a swamp located in modern day Fairfield. Most of the warriors were slain, while the women and children were taken captive. Sassacus himself escaped and threw himself upon the mercy of the Mohawks in upstate New York, and they in turn sent back his severed head and hands to Hartford as a present to the colonists.

The scattered remnants of the Pequots were hunted down by the Mohegans and the Narragansetts, and there was a steady delivery to the colonists of severed Pequot heads and hands as proof of their diligence. The Mohegans incorporated some of the Pequots into their own tribe to bolster their rather slim numbers, but many Pequots were enslaved, some of the women as domestic slaves in the houses of the colonists, while others were shipped off to the West Indies and Bermuda. Seventeen Pequots were sent to a short-lived English colony off the coast of Nicaragua and exchanged for African slaves, who are believed to be the first enslaved Africans imported into New England.

The last 200 or so Pequots in Connecticut that had eluded capture or death eventually surrendered in 1638. These were divided up and awarded to the allied tribes as spoils of war. In an attempt to completely eradicate the Pequot nation from existence, the 1638 Treaty of Hartford signed by the Connecticut Colony, the Mohegans, and the Narragansetts proclaimed that the last remaining Pequot survivors were forbidden to ever return to their lands, speak the Pequot language, or refer to themselves as Pequots ever again. The former Pequot territory fell under the control of the Connecticut Colony, opening the door for colonization and expansion.

In 1948, the United Nations defined genocide as acts “committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” Some scholars say the Pequot War falls short: there was no overarching plan to exterminate every single Pequot, and some also cite the presence of Native American allies amongst the colonists, and the fact that it was an action taken against only one tribe and not the entire culture and ethnicity of Native Americans overall. For me, minimizing what was done to the Pequots by lumping them into a larger Native American cultural identity is unconvincing. The complete and indiscriminate slaughter at Mystic, followed by the attempted eradication of all traces of Pequot identity, seems to pretty squarely fall under the definition cited above, even if the scale pales in comparison to the atrocities committed in the name of ethnic cleansing in the 20th century.

After the war, Captain Mason was promoted to major for his services, and was awarded numerous land grants. In 1645, his old commander from the Thirty Years War, Sir Thomas Fairfax – now the commander-in-chief of the parliamentary army in the English Civil War – sent a letter urging him to return to England and fight for the parliamentarian cause against King Charles. Mason would certainly have had a high command, as Fairfax was in desperate need of experienced military officers (Fairfax’s second-in-command at this time was Oliver Cromwell, who had no military training prior to the civil war). But Mason declined, instead taking command of Fort Saybrook in 1647 and becoming the chief military officer of the United Colonies of New England as well as Deputy Governor of Connecticut. In 1659, he, along with William Backus and many other of our ancestors, founded Norwich after purchasing the land from his old ally from the Pequot War, Uncas. In 1889 – during the “statue craze” that saw the erection of statues of Confederate generals all across the South – a statue of Mason was erected on the site of the Mystic Massacre, where it stood until 1996 until it was relocated to Mason’s hometown of Windsor.

Uncas and the Mohegan tribe went from tributaries of the Pequots to becoming tributaries of the Connecticut Colony. The Mohegans remained the loyal allies of the colonists, siding with them against the Narragansetts and the majority of the indigenous tribes of New England in King Philip’s War forty years later – New England’s bloody second and final war between the Native Americans and the colonists. Uncas and Mason remained close to the end of their lives, and their ancestors retained ties for generations. The Mohegan Indian Reservation continues to exist today on the outskirts of Norwich, where the Mohegan Sun casino is located.

Our ancestors from Hartford, John Clark and William Pratt, did well for themselves after the war. They were likely personal friends of John Mason, for both of them ended up in Saybrook in the 1640s when Mason took command there, and Clark seems to have accompanied Mason to Norwich. Clark was one of the petitioners of the charter to King Charles II in 1662 that legally established the Connecticut Colony. Eventually he moved on to Milford, where he died in 1671. William Pratt stayed in Saybrook, becoming a lieutenant of the local militia in 1661 and representing Saybrook in the General Assembly of Connecticut in 23 sessions between 1666 and 1678. He also must have had personal ties to Uncas, as he was named in the will of Uncas’s third son, Attawanhood. As veterans of the Mystic campaign, both Clark and Pratt would have been considered heroes, and they received generous land grants in commemoration of their service.

As for the Pequots, they were essentially eliminated as a military and poltical force, but as a tribal and cultural entity they were more difficult to erase. The Pequots that were placed under the control of the Mohegans and Narragansetts were eventually removed from their custody and placed on two separate reservations in Connecticut, the Manshatucket Reservation and the Pawcatuck Reservation. By 1910, U.S. census records indicate there were only 66 Pequots remaining in Connecticut, though their numbers grew substantially over the next century. Today, the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation is home to the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center, as well as the Foxwoods Resort casino located about six miles east of Mohegan Sun, the casino run by the Mohegans – plastic casino chips replacing sea shells as currency in an economic competition for gambling dollars, a faint echo of their tribal enmity and warfare on the same lands from nearly four hundred years ago.