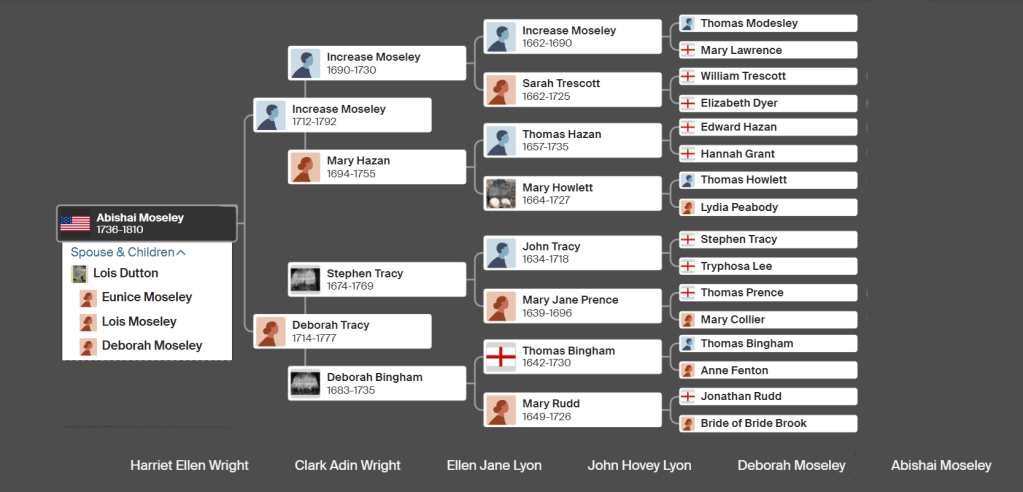

In what is now East Lyme, Connecticut – located halfway between Saybrook and New London – runs a small stream called Bride Brook. The story of how Bride Brook got its name comes to us from Francis Caulkin’s History of Norwich first published in 1845.

According to Caulkin, the small brook was the site of a wedding in the winter of 1646/47. Both the bride and groom were residents of Saybrook, where there wasn’t a qualified magistrate to marry the couple. By this point Saybrook had been absorbed by the Connecticut Colony, but a snow storm prevented travel between Saybrook and Hartford. So the couple sent word to no less a personage than Saybrook’s founder John Winthrop Jr., who had recently established neighboring New London (called Pequot at the time), asking him to perform the ceremony. That apparently created a legal problem, however – New London was initially established under the jurisdiction of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and Winthrop felt he could not exercise his function as a magistrate in Connecticut territory.

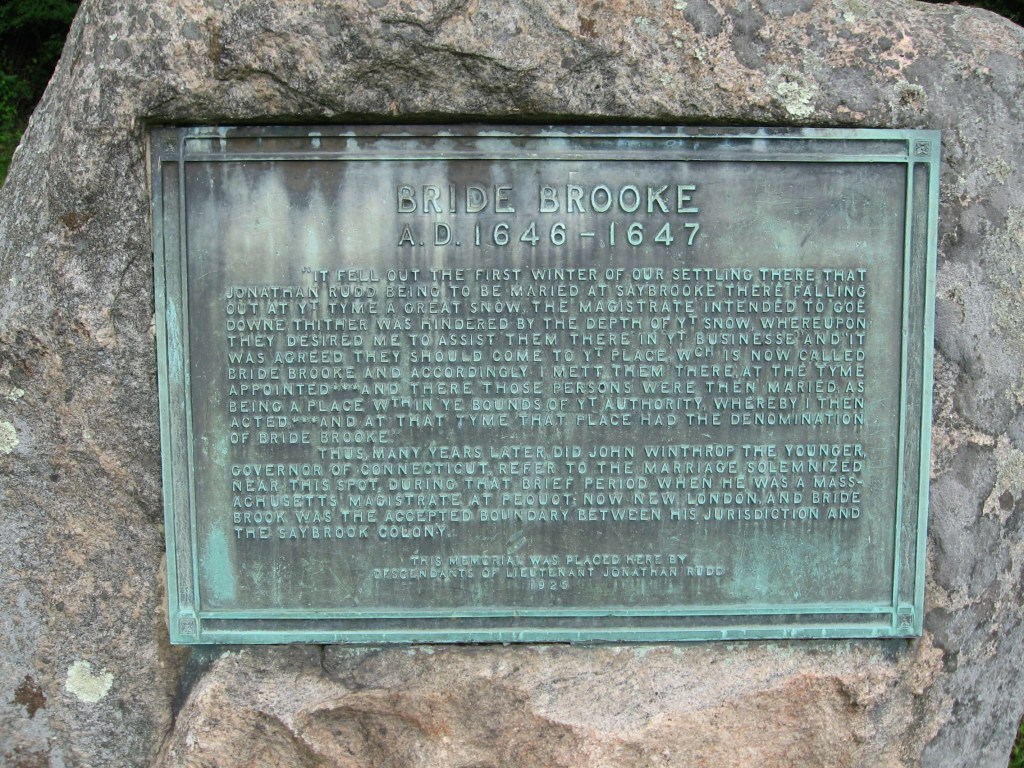

Undeterred, Winthrop came up with the novel idea that he could marry the couple as long as he was in Massachusetts and they in Connecticut, so the parties met at a stream that was deemed the territorial boundary between the two colonies – the bride and groom on the west side of the stream, and Winthrop and his party on the east side. And so the marriage took place, the couple became Mr. and Mrs. Jonathan Rudd, and the stream was thenceforth dubbed Bride Brook. New London would be annexed to Connecticut a year later, but it seems the young colonial lovers couldn’t wait that long.

Since then, the romantic tale has captured the imagination of many local residents and Rudd descendants. The ceremony was re-enacted at Bride Brook in 1925 and again 1935, and a commemorative plaque was installed on the supposed site that still exists today. The story also inspired a 22-stanza romantic poem written by George Parsons Lathrop that appeared in the Atlantic in 1876. Lathrop paints an idyllic picture:

But “Snow lies light upon my heart!

An thou,” said merry Jonathan Rudd,

“Wilt wed me, winter shall depart,

And love like spring for us shall bud.”

“Nay, how,” said Mary, “may that be?

Nor minister nor magistrate

Is here, to join us solemnly;

And snow-banks bar us, every gate.”

“Winthrop at Pequot Harbor lies,”

He laughed. And with the morrow’s sun

He faced the deputy’s dark eyes:

“How soon, sir, may the rite be done?”

“At Saybrook? There the power’s not mine,”

Said he. “But at the brook we ’ll meet,

That ripples down the boundary line;

There you may wed, and Heaven shall see ’t.”

What would seem like merely a fanciful legend is bolstered by the fact that Winthrop himself retold the story in a 1672 deposition during an attempt to try to settle a boundary dispute between farmers from New London and Lyme over the right to cut hay in the disputed area. Despite Winthrop’s creative legal mind – or maybe because of it – Winthrop’s retelling of the Bride Brook wedding didn’t conclusively establish the boundary between the two towns. After subsequent petitions to the general court in Hartford failed to produce an agreement, the two sides finally decided to settle the matter by a fist fight between two picked champions from each town (Lyme won).

We don’t know very much about the groom, but the scant information we have of him doesn’t conjure up the traditional image of Puritan propriety. Who Jonathan Rudd’s parents were, where in England he came from, and the circumstances that brought him to Connecticut are all unknown – we first hear tell of him in April 1640 when he appears before a Hartford court with other youths for “being intimate” with a Mary Bronson. He then appears in the newly established New Haven colony, where he was fined twice in 1644, first for maintaining defective arms, and then for attending a drinking party.

Rudd next turns up in Saybrook, where he seems to have made a more respectable show of things. Shortly after his picturesque wedding in the snow in 1646/47, he is listed in a 1648 Saybrook town meeting as one of twelve men awarded land east of the river in what would become Old Lyme. The list isn’t in alphabetical order, and the two last names on it are William Backus and Jonathan Rudd – so if the list is ordered by lot assignment, this may indicate that the two were neighbors. Later, in 1652/53, Rudd is listed alongside Thomas Tracy as one of two lieutenants to Captain Mason responsible for fitting out six “great guns” for the defense of Saybrook.

Both Mason and Tracy, as well as William Backus and four others among the twelve “Old Lyme” settlers, would go on to become first proprietors of Norwich in 1659. Given his connections to these men, it seems likely Rudd would have joined them in Norwich if he hadn’t died from unknown causes a year earlier. Connecticut probate records indicate that Norwich founder Rev. James Fitch took in his six children, so Rudd’s offspring ended up in Norwich all the same, and that’s where Rudd’s seventeen year-old daughter (and Wright ancestor) Mary would wed Thomas Bingham in 1666. Since Thomas Bingham was William Backus’ stepson and living in his household at some point after 1648 – also in the Old Lyme section of Saybrook and possibly next door – it seems likely the two knew each other growing up.

As for the bride of Bride Brook, we know virtually nothing about her. Tradition has it that she was named Mary, and some early genealogists claim she is Mary Metcalf, and others say she is Mary Burchard, but conclusive evidence is lacking. While the names of colonial men appeared in court records and town meetings as they went about their more public lives, colonial women would be home managing domestic affairs largely out of the public record, and when they did appear, it was as the wife of their husbands.

Even when their original surname is known, we don’t always know what happened to them. In colonial America, a married woman’s personal property came under the control of her husband, placing her in a system of almost completely dependency under the law. Married women generally did not write wills. We often learn that they have outlived their husband only by the husband’s bequest to them, but if the wife dies first there is sometimes no record of it, and in those cases we may only find out that the first wife has passed when the husband remarries. That wife, in turn, might outlive her husband, but if she were still of child-bearing age she would inevitably remarry and start the cycle again. At this point we might know her only by her previous husband’s surname, her own parentage having been effectively erased.

Those who died before their husbands often did so in childbirth. The chance of dying while giving birth in colonial New England is estimated as between one and one point five percent, but colonial women gave birth many times – upwards of ten births was not uncommon – and some estimates indicate that one in eight women died in such a way. We know the bride of Bride Brook had at least six children that survived infancy between 1647 and 1658, and then no more is known of her. She does not appear as a beneficiary in Jonathan Rudd’s will. Perhaps she died giving birth to the sixth child, or alongside a seventh.

If so, her daughter Mary would be more fortunate. After three decades in Norwich, the Binghams helped settle Windham in 1693, and a gravestone inscription there indicates that Mary Bingham died in 1726 at the age of seventy-seven, ending sixty years of marriage (Thomas Bingham died four years later at the age of eighty-eight). Between the age of eighteen and forty-one, Mary Bingham gave birth to eleven children, all of whom lived to adulthood. The eighth, Deborah Bingham (b. 1683) would eventually lead to us.

With that, I’ll end with the final stanza of Lathrop’s poem commemorating the Bride of Bride Brook- and the men who remembered her by forgetting her:

“But none can tell us of that name

More than the ‘Mary.’ Men still say

‘Bride Brook’ in honor of her fame;

But all the rest has passed away.”